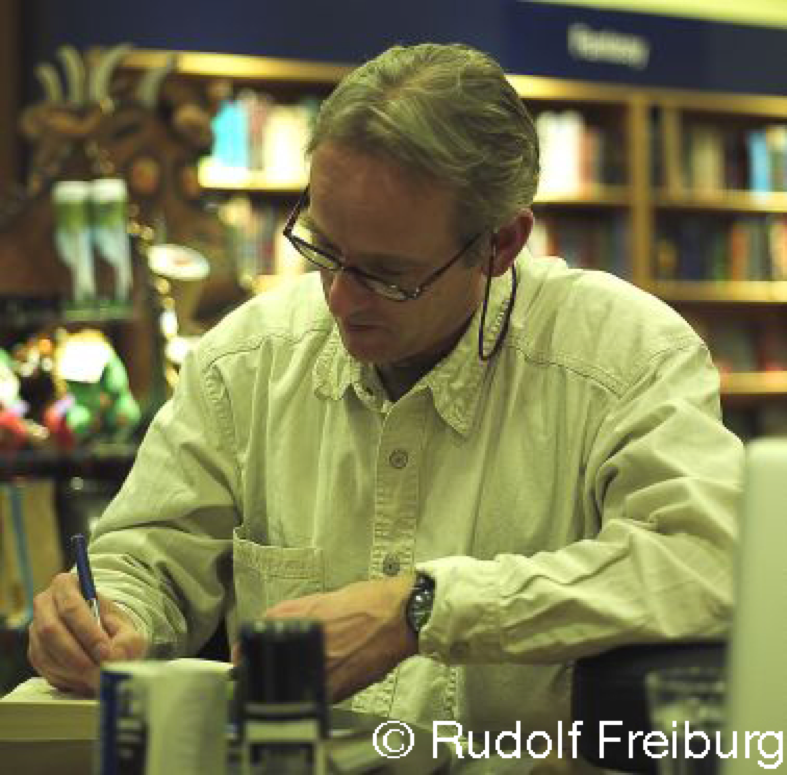

Ein Gespräch mit dem Kultautor Jasper Fforde

von Susanne Gruß, Nadine Böhm-Schnitker

Der als Kultautor gefeierte Jasper Fforde, der für seine stetig wachsende Leserschaft Wettbewerbe veranstaltet, Taschenbücher mit eigens angefertigten Stempeln einzigartig macht und sogar seinen Schreibtisch gewinnbringend versteigern kann, steht dem Konzept Kult kritisch gegenüber. Mit Ironie und Witz parodiert er mit seiner Wortneuschöpfung des „postkonstruktivistischen Demodernismus“ den wissenschaftlichen Theoriekult, um dem gegenüber herauszustellen, dass das Geschichtenerzählen eine menschliche Grundeigenschaft darstellt. Im Schau-ins-Blau-Interview spricht er mit Nadine Böhm-Schnitker und Susanne Gruß neben der Frage kultischer Autorenverehrung über seinen literarischen Werdegang, seinen Kontakt zu Leserinnen und Lesern, die Unterschiede zwischen literarischer Produktion und literaturwissenschaftlicher Analyse und über gute Literatur.

SCHAU INS BLAU: Do you have a favourite question? If you do not, what is your least favourite question?

JASPER FFORDE: I don’t think I have either, to be honest. I kind of think that there is actually only one question you want to ask an author, and that is ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’, and in fact every single question I get asked is actually a sort of variation on that theme. My favourite questions, I suppose, are the ones which are about some sort of very small esoteric part of one of my books; this actually allows me to think about how I wrote it, because as counter-intuitive as it may sound I learned to write without knowing how I learned to write. I just sat down and wrote books but I have no training in writing. I didn’t go to university, I left school at the age of eighteen with a great C in art; the last time I learned any English at all was for my GSCEs at the age of sixteen, when I got a C in O‑level English. I have got no training as an author at all so I just sat down to write books one day, and eleven years later I got published. But sitting in a room on your own inventing all these plot devices in third-person narratives and things like that, I had no names for them at all. So when I became published as an author and I said ‘Ok, any questions?’ when I was getting talks, and people said ‘Why did you do this, why did you do that?’ – then all of a sudden I had an opportunity to question how I wrote the books that I had written, and it has been a huge education for me. So actually I’ve run my career on the reverse in that I wrote the books and then figured out how to write afterwards through being asked bizarre questions.

And that is why sometimes bizarre questions are the best and I get asked these very, very strange questions about very small parts, very small sub-plots which have an interesting little sort of twist to it that is slightly ambiguous, and I get asked, ‘Why did you do this, why did you do that, it must be because of so and so and so and so’. So, it is sort of reverse engineering with my books. This goes to show, of course, that I am not a vast intellectual superior or anything at all. What it says is that story telling is clearly inherent in human beings.

SCHAU INS BLAU: Man is a story-telling animal…

JASPER FFORDE: Yes, and you don’t need to actually go to school to learn any of this, you just have to be human and you have to have time on your hands and a keyboard. It probably doesn’t sit well with academics, but you can do it and all that ‘postconstructional demodernism’ which my books are imbued with… if someone says, ‘Ah, tell me about intertextuality’, then I go ‘I have no idea what you are talking about’. I do now because I have learned what it means, my books are full of intertextuality. I had no idea what it was or where it comes from or anything. I just thought it amusing and fun. So that is the questions I like getting, the ones that allow me to find out why I wrote the books that I wrote.

SCHAU INS BLAU: Your work has mostly been described as fantasy literature or comic fantasy or something along these lines. Where on the relatively broad spectrum of fantasy literature would you situate yourself?

JASPER FFORDE: Again, I don’t know. I’m not someone who is beholden to genre, I think genre is the measles of literature, I really do. It allows people to be narrow in their book choices when they should be broad, I think broad book choices are far better. The thing about genre is it gives people an excuse to stay within one island in a vast archipelago of fascinating concepts and interests within the literary world. So, when I set out to write I don’t particularly have any kind of genre or subgenre. The good thing about my Thursday Next books it that they are clearly fantasy, obviously, but they can actually encompass any number of genres. In fact The Eyre Affair encompasses horror, sci-fi, literature, romance, crime, that is five genres. I like to think of my books as multi-genre. Even my dystopia book, Shades of Grey, I regard as a social thriller.

SCHAU INS BLAU: I still think you do work with genre quite a lot because if you think about the Nursery Crime novels, for example, they work like relatively traditional crime novels but with a comic twist.

JASPER FFORDE: Yes, they are. The Big Over Easy, the first Nursery Crime book, is very obviously a crime book, but it really takes some very well-aimed jabs at what I think is a very tired genre. In fact, in The Big Over Easy, we have all kinds of jokes at the expense of the genre, yet at the same time, being a member of its own genre, it does in fact – being itself – make fun of itself all at the same time, which is a kind of reverse loop that I actually like to use in a lot of my books. In the Thursday Next books and the Nursery Crime books there are as many stories about stories as there are stories about how we tell stories, how we understand stories and the rules of story telling, story telling grammar, if you like, which seems very fixed – but the fact that it is very fixed also means that you can play with it in wonderful ways, and you can take these ideas and make them very malleable and tell these stories about stories. I don’t know quite where they sit for genre but it is clearly fantasy, metafiction, fiction about fiction.

SCHAU INS BLAU: Would you consider yourself a cult author or does ‘cult’ mean anything to you?

JASPER FFORDE: Cult to me has negative connotations against readers. That might be just an English thing. It tends to, I believe, place what I call enthusiastic readers who embrace the world that I have created… it’s slightly demeaning I feel. So I tend not to, try not to use that word at all. It also makes readers seem disciples, which I think is wrong. I do think that the relationship between a writer and a reader is quite basic, fundamental. I regard myself not as a literary author, but as working essentially in the entertainment business rather than working in the literary world. We leave that up to the big-name authors with their human drama books where they tell long and slightly meaningful stories. I tend to entertain. In that respect, I think the contract one has with readership is very basic. It is that people get out and spend hours earning their hard-earned cash and they hand it to me and in return it is incumbent to me to entertain those readers for as long as it takes to read a book. And in that respect, I like to think of readers as being people essentially part of that contract and I think perhaps the notion of cult it just slightly demeaning.

SCHAU INS BLAU: One could say, however, that you have a kind of dedicated followership. Your website, for example, allows for the formation of audiences and gives them options for exchange. There are forums, there are competitions, the so called ‘Fforde fiestas’. Recently, you auctioned your desk which might have some cult status to someone inclined to bid a high price precisely because it is Jasper’s desk. Even if you are critical of the notion of cult, could you describe whether your audiences are to some degree a followership? And what role does the website play in that context?

JASPER FFORDE: I’m still sort of avoiding this, I suppose. Difficult one to explain really. I think the thing about my readers, the people who read my books is that they totally get where I’m coming in. And I think when you are reading a book that seems very, very relevant to how you feel, how you’ve run your life, your sense of humour, when you feel yourself in concordance with someone, in agreement with someone, then you can get along with him. It is like when you meet someone at a party or wherever, and all of a sudden you click and you gel. And I think when you are reading a book which has a lot of different themes in it which you might share with the author then you do feel a certain degree of warmth, obviously, towards the person and everything else. I think when someone writes the sort of books that I do, a lot of it is of shared experience and I am putting a lot of my shared experience on the page and people are reading it and agreeing and saying, ‘Yes, yes, yes, this is totally how I see it as well’. I think that is the reason why I do have an enthusiastic following but I’m still sort of wary of the whole cult thing.

The internet, I regard my websites as a kind of after-sale service, really. Because I only bring out a book once every sort of nine months or so, or two books a year, and in between you may want to know what is happening in the Castle Fforde, and you can. I run competitions and give give-aways and all sorts of stuff like that. It is just a kind of way of giving a little bit more and thanking people really for supporting me and my family for all these years – eleven years now, you know, I have been living off the generous contribution of people who read my books. I think there are many authors who forget that and they put themselves a little bit loftily above the readers and I think there is a little bit of contempt. But I hear authors saying, ‘Oh, I don’t do signings, I won’t inscribe names in books’, and I think ‘you miserable bastard, that is so contemptuous of these people who are supporting you’. You should certainly go on out there. You don’t have to tell everyone about your private life or anything, but you should certainly go out there and meet people. Unless you are physically unable to do so, then you should certainly tour. If you sell large quantities of books, I think you owe to your readers to tour and speak to people, meet people, simply as a way of just saying thank you. And there are a lot of authors who don’t. And I think it’s contemptuous, to be honest.

SCHAU INS BLAU: You do your website yourself?

JASPER FFORDE: Yes, I do, and it shows. It is quite funny because nowadays lots of people are web authors and a lot of people understand about html and everything and they look at my website and they go, ‘Jasper, you really haven’t moved with the times’, and I say, ‘No, I haven’t’, because I learned html about ten years ago and apart from justified text as a sort of major technical breakthrough in about 2005 nothing else has changed. But people seem to like it because of that, because that is how websites used to look in the early days of the internet. When Jasper Fforde went online, there were certainly under a million websites and ‘Jasper Fforde’ only had one hit, and now it has any number of millions. And it is nice and easy to use, html is very easy to use and I can just change a page just like that, you know, very easily. It doesn’t need bells and whistles. All it is is text and pictures. It doesn’t need pull-down menus, why would it need pull-down menus and all sorts of that kind of nonsense. So I just leave it as it is, very old-fashioned, and I can do it and debug it myself, it is dead easy.

SCHAU INS BLAU: It has become a work in its own right, because it actually complements the books and allows readers to upgrade their books, for example.

JASPER FFORDE: Yes, you can do all kinds of things. I mean it’s now vast. Every now and again we do an upgrade to the basic page and it is over a thousand pages, so it really is at least two books’ worth there, and I know people who have said to me, ‘I have read your website, it took me months to go through it’, and I say, ‘Oh, did you find the page the goes bladibladibla’ and they went, ‘Ugh no, I didn’t find that one’ and I said, ‘Well, keep on hunting’, because it is very spread. The index isn’t quite there so there are little corners at the Fforde website you can actually hunt down just through clicking links and everything. So it is quite an exploration. And I also think there is a little bit extra about it … and I think it is important – if you are going to have a link with readers, whether you are going to tour, whether you do the postcard giveaways I do, the book stamps I do, talking to people is all very important, but if you want to have a link to readers through the website you have got to write it yourself, because if you do it through your publishers then there is a disconnect because it goes through a third, a fourth or even fifth party and it becomes corporate. But when I write my website it is all me and I and we and it’s got a few spelling errors. I think you’d have to hunt to find a website which was run solely by the author and did actually reflect the author quite as well as jasperfforde.com does with all its foibles and problems and old html. So I’m quite proud of it, I kind of like it. It is genuinely me and I think that is important.

SCHAU INS BLAU: Do you have an intended audience?

JASPER FFORDE: No, and I think it is very important that one doesn’t. If you start writing with people in mind then you are not writing for yourself. I think it is very important that when you write a book you write it primarily for an audience of one. I’m writing constantly to try and make myself laugh.

SCHAU INS BLAU: You are the one who gets all the clues.

JASPER FFORDE: I’m the one who wants to be laughing and crying and all that sort of stuff. I want to do something that really works but I can only do that for myself. I think it is important to do that because once you start writing what you think people want to read then you might get into a sort of downward spiral of writing rather formulaic me-too books. Although I obviously know the readership is there, and you can play on what the readers expect because then you can wrong-foot people; you really want to wrong-foot people in a good way when you are writing crime books or my kind of thrillers, you want to do twists and turns and everything. But now I know there are readers out there who know how I write, and that is quite an interesting way of wrong-footing readers because I can actually do something and they go, ‘Ah it is a Jasper book, I know something is going to happen’. But of course I know that they know that, so I can then do something completely different. There is a character in the last Thursday Book called Red Herring. Now the question is, of course: Is Red Herring a red herring? Now, if it was my first book, Red Herring would of course be a red herring, but in the latter books people would look at Red Herring and think ‘Ah, that’s a red herring’, but the red herring is the fact that he is called Red Herring, so he is a red herring but you thought he wouldn’t be. So that’s working – a bit complicated – that is working on readers’ expectations, not just because of the book but because they know my method of writing and my style of writing. So I know the reader is there but I think it is very important that authors write what they want to write and not to be perhaps swayed into doing either popular stories or easy solutions to what they are doing or doing the same book again. There are a few authors out there, I won’t mention any names, but they wrote one book and then rewrote it, that’s probably a bit of a cheat then.

SCHAU INS BLAU: You have a lot of canonical references in your books, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre or Shakespeare’s Hamlet for example, but also very popular references. Would you say that different audiences respond differently to your books?

JASPER FFORDE: Oh yes, definitely. Someone said to me, ‘I don’t read fantasy, but I read you’, and I go, ‘Well, this is fantasy’ – ‘No, no, I don’t read fantasy’. They’re obviously pulling into the humour, the comedy, the charm, the spark or whatever you have in it. I do get people who buy my books for crime, I get people who buy my books for the sci-fi, I get people who buy my books because they like Thursday as a feminist icon, all sorts of different reasons. And that’s terrific, because instead of one-crackers you get many different types of people who read the books. When I go to the States, there are a lot of independent booksellers out there and they are very good at events – they’re getting better in the UK, actually, I must say, there’s been a big resurgence in the independent book sector – and I can go to Houston, for example, and I’ll talk at a crime book shop, and then I go to San Diego and I talk in a fantasy bookshop, and then I go up to, say, San Francisco, and I talk in a crime, fantasy, and sci-fi bookshop, all of whom embrace me as one of their own. But none of these, I can say, is the particular genre of my books. A lot of people get a lot of different things out of them and that’s the glory of writing a book that is much, much broader than the usual genre, you know, stick to this, we’re doing human drama, it’s about a girl-man-problem, father with cancer, usual stuff.

But also, there are a lot of people who won’t read my books because they don’t like that kind of sprawling mess of multiple plot strands, and silliness, and people who won’t read fantasy. There are many, many people who will not read fantasy, simply because they think it’s goblins and wands, firing arrows. There are lots of people who won’t read science fiction, because they think it’s space travel and thralls, you know, aliens, and crime has only recently come out of the dustbin to which a lot of these genres have been dispatched, and I think it’s kind of unfair. And, certainly, when I was writing The Eyre Affair, I had this notion that it would be like a sort of train station with lots of different trains in it and that you could come and arrive on a sci-fi train and then take the fantasy train out of it. Because I was finding that a lot of different people who were attracted to it, coming in because it was about sci-fi and then saying, actually I really enjoyed the fantasy aspect about it, so let’s look at fantasy books.

SCHAU INS BLAU: You also have a very broad academic readership…

JASPER FFORDE: That surprises me!

SCHAU INS BLAU: You do, and I read articles about your work which apply postmodern theory, or theories of immersion, theories of adaptation, of intertextuality, metalevels etc. on your work. Are you interested in academic discussions of your work?

JASPER FFORDE: Yes, when I can understand them. I have been challenged on several academic panels who wanted to talk to me at length about my books, and I had to say that I didn’t understand what they were actually talking about, and a lot of their references I did not understand. And they seemed slightly bemused by this, and wanted to know how I could write books about intertextuality without knowing what intertextuality is. And my answer to that is, much like philosophers who claim to be inventing a new style of thought, I tend to be more of the opinion that, in fact, that they are simply mapping the way thought happens to be going at the time. It’s like writing down rules of grammar. The rules of grammar don’t actually tell us how to talk. Rules of grammar just explain the way that we do talk. So, I think, sometimes, academia studies something, and then believes that it’s sort of creating what it’s studying.

SCHAU INS BLAU: When it’s done badly.

JASPER FFORDE: When you sort of run ahead of yourself, and instead of explaining something, just adding new theories to it and saying this is what’s happening, and perhaps it isn’t. I come from a totally non-academic background. But that point alone shows you that someone who is non-academic can write books that people actually want to read, but can also talk vaguely intelligently about them. Stories are in us, they are part of us, and we are defined by stories as human beings, we couldn’t make a move without them. We learn by them, we are entertained by them, we can converse by them. I am telling stories now, I am telling a story about how I learned to write, and you’re interacting with the story by bringing a dialogue into it.

SCHAU INS BLAU: I would like to bring in another academic approach by a critic who wrote about the use of genre and the role of the canon in your books. You mentioned before that Thursday Next might be seen as a feminist icon. Now, would you say that the genres comedy and romance might undermine Thursday’s feminism as both genres make characters end up married, thus ratifying the heterosexual couple? Might comedy and romance – and possibly also the dominant reference to Jane Eyre read as a conservative text – actually thwart the feminist point that you are making?

JASPER FFORDE: I can see the point. But you would have to accept first of all that marriage is somehow not a feminist institution. That clearly sounds to me where the critic is coming from; in the days when being married meant that you had to give up your cash and property and rights to your spouse I think the critic would be quite correct. But nowadays I don’t suppose… I mean is marriage to do with patriarchy? It shouldn’t be. And I don’t accept that it is for one moment. My wife didn’t marry me and say, ‘Ok, I’ll have to give up my independence now I am married’. She took my name because I have a better name, you know, Fforde is a more interesting name than Roberts. If I had been called Roberts and her mother’s name was Graytracks, which is a really cool name, I would have taken the Graytracks. So I think from the very small thing you told me, my initial sort of thinking about it would be that I think the reviewer has a slightly skewed version of marriage, as being a dominant and possessive thing for the male, and I don’t think a good marriage is, it’s a partnership. That is the point I would make about it. But I’m a bloke…

SCHAU INS BLAU: It probably also depends on how you read Jane Eyre. I remember you called Jane Eyre a protofeminist heroine yesterday and if you see her starting from that stance, it’s a completely different viewpoint. When I read Shades of Grey, I felt that it is very bleak and grim at times, also tapping into different genres apart from the romance, such as dystopia for example. Is that you going into a more serious direction?

JASPER FFORDE: I could talk for hours about Shades of Grey, Shades of Grey was a departure for me as a writer. As a book, it was not using other people’s characters, it was using my own characters, and it was also an experimental book. The Eyre Affair and the The Big Over Easy, although not looking so experimental now, were at the time when The Eyre Affair was published in 2000 very unlike anything that had come forward, you couldn’t mix Jane Eyre with werewolves and time travel in the same book, just didn’t happen – not in a main stream book, published by Hodder & Stoughton, one of the leading six publishers in the UK. It just wasn’t the sort of book that came out at the time. Nowadays, it is probably fairly normal.1 But the thing about Shades of Grey is that, like in The Eyre Affair, I was trying to mix different strands of pop culture that I think are of equal importance – see, I would put the Muppets as nearly as important as Charles Dickens when it comes to cultural tags and importance within humans. Star Wars is about as important to a lot of people as … certainly it would be above Goya but certainly perhaps below Carravaggio, I’m not sure. Do you see what I mean? People go like, ‘Oh Star Wars, it is just a load of rubbish’, and you go, ‘No, actually it is a cultural marker, it is of vital importance to a lot of people’. A lot of very interesting thoughts and things have derived from the whole Star Wars culture, in the same way that things derive from painting and architecture and everything else, Richard Rogers or whatever. They do have an equal weighting. So there is that aspect within The Eyre Affair that says, ‘no, I think science fiction values, literary values can go hand in hand, we can have high-brow jokes and low-brow jokes work together’.

So Shades of Grey, there were elements of risk within writing that book, and I was trying to put very serious subjects alongside with humour as well, so really trying to mix the two as much as I could to see basically if it could be done and whether it is going to work. When you write a novel, especially one that is kind of experimental like Shades of Grey is – when I start writing it I won’t know for two years whether it’s worked or not; because I can think it works, it works for me, I like it, it has done pretty much what I set out to do. But until it is actually out there and people look at it and read it and go, ‘Erm, no, not really, or, hm, yeah’, and even that might not happen straight away and Shades of Grey may not hit its stride for another ten years or so, maybe when people have caught up with it or society has changed or whatever, but the major problem, the stumbling block with Shades of Grey was that people didn’t understand whether it was comedy or whether it was very serious. And I am saying it is both and I don’t see any problem with that. I can totally acquaint being very silly with being very serious. Essentially I think humans are very funny, very bizarre, very random; very funny, but capable of the most appalling sadism, and if there is a broad theme within Shades of Grey it is that: yes, we can have comedy, but there is tragedy as well, and sometimes they are so close that it is almost impossible to see. So there are a lot of very serious themes in Shades of Grey, things that people don’t generally talk about like marriage markets, we may think we are free to marry who we want, but clearly we are not, we marry within very clear socioeconomic boundaries, reproductive politics again popped into the floor in Shades of Grey quite a lot which no one really now talks about. And all sorts of interesting social aspects, but again hidden among this rather strange sort of story which has a lot of slapstick comedy in it. Sorry, what was your question again?

SCHAU INS BLAU: Whether you are becoming more serious.

JASPER FFORDE: There is an element of seriousness in all the books. There are themes that run throughout all the books. Within the Thursday-world I try and promote themes of tolerance and diversity and social inclusion, but you don’t want to preach it, because then it is tiresome. There is nothing more tiresome than having an author stand on a box, especially a fiction author, or any author actually, to stand on a box and say this is how we should all behave because I say so. I think the job of any author or anyone within the creative industry like that is to give a small puff to that large cloud and hope that it goes in the direction that you want it to go but your contribution is minimal. But if you have enough people you can just sort of push in that direction, and you can hopefully make things turn out for the better.

SCHAU INS BLAU: One last question about the Thursday Next series. What I really liked in One of Our Thursdays is Missing is the idea of raw metaphor and that there is a war about raw metaphor, like a war about raw materials. Would you say that metaphor is the central thing about literature, is it an argument about what literature is all about?

JASPER FFORDE: Yes, absolutely. One of the first things one learns when writing is that the first thing you don’t want to say is what the story is not about, what the story is about. If you have got two people with dialogue the real story is not what they are talking about, the story is something else. And that is inferred narrative or whatever. The best stories, I think, are the stories that everyone is dancing around, that are never mentioned, but you know what is going on. And we do that all the time in real life, everyone has an agenda and when I am writing I think, ‘What do these people actually want, and how would they couch their language in that particular area?’ I was kind of thinking about the difference between metaphor within fiction and non-fiction. Because, of course, in non-fiction you don’t want to have metaphor, in science you definitely don’t want to have metaphor, but in fiction you want to have as much as you can and if there is a shortage, of course this would cause wars, and it is like when there is a shortage of materials to cause wars but it is a nice sort of satirical jab. It is important.

SCHAU INS BLAU: Thank you very much.

JASPER FFORDE: You are very welcome. Thank you.

Anmerkungen

- Fforde verweist hier mit den literarischen ‚Mash-ups‘ auf einen aktuellen Trend auf dem anglo-amerikanischen Buchmarkt. In Mash-ups wie Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (Seth Grahame-Smith, 2009) – der Titel ist eigentlich Erklärung genug – werden Originaltexte beliebter ‚Klassiker‘ von Jane Austen oder den Brontë-Schwestern mit Vampir‑, Zombie- oder anderen Monstergeschichten neu kombiniert und vermengt und so für einen populär-kulturellen Markt angeeignet. Lizzie Bennet wird so zur furchtlosen Zombie-Killerin, während in Jane Slayre (Sherri Browning Erwin, 2010) Jane Eyre zum viktorianischen Äquivalent von Buffy the Vampire Slayer stilisiert wird.

Nach einer Karriere als Kameramann betrat der 1961 in London geborene Jasper Fforde 2001 mit The Eyre Affair die literarische Bühne. Gefeiert als „a born wordsmith of effervescent imagination” (C. Hardyment, The Independent) wurde Fforde schnell zum Kultautor diverser Romanserien. Die Thursday Next-Serie, die mit The Eyre Affair begann und mittlerweile sieben Romane umfasst – The Woman Who Died a Lot erschien im Juli 2012 –, folgt der Figur Thursday Next auf ihrer fantastischen Reise durch die (Parallel)Welt der Literatur. Darüber hinaus veröffentlichte Fforde die ebenso hochgradig intertextuelle Nursery Crime Division-Serie, eine Parodie des Detektivgenres, den ersten Band einer etwas ernsteren dystopischen Serie (Shades of Grey, 2010) sowie die Last Dragonslayer-Triloge für jüngere LeserInnen. Ffordes Werk wird häufig dem Fantasy-Genre zugerechnet, seine Texte stellen allerdings hybride Formen dar, die sich unter anderem des Detektivromans, der romantischen Komödie und der Science Fiction bedienen. Fforde kann als Wegbereiter der so genannten mash up-Literatur gelten und verbindet mit wunderbarer Leichtigkeit George Eliot und George Lucas, Dickens und Dodos. Fforde lebt mit seiner Frau und den gemeinsamen Kindern in Wales.